The Night Watch, 1642 by Rembrandt van Rijn

The entry of Marie de' Medici, the French Queen Mother, into Amsterdam in 1638 was a great event for the militia companies, who took extensive advantage of the opportunity to put on a show. Perhaps inspired by the pomp and circumstance

of that occasion, the militiamen of the Arquebusiers Guild decided shortly afterwards to decorate the new assembly hall of their headquarters with a series of pictures. Each company was to have a portrait made of its own group; above the

mantel was to be a group portrait of the senior officers, the Doelheren.

The commissions for the paintings went to six different painters, Captain Frans Banning Cocq's company falling to Rembrandt. Apart from Captain Cocq and Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburgh, sixteen other militiamen wanted their portraits

included, each paying a sum of about a hundred guilders - some slightly more, some less, depending upon where they were placed in the final picture. The shares of the Captain and the Lieutenant were of course the greatest.

In Frans Banning Cocq's family album there is a drawing of Rembrandt's group portrait, accompanied by a precise description: 'The young squire of Purmelant (Banning Cocq) as Captain orders his Lieutenant, the squire of Vlaerdingen (Van Ruytenburgh), to advance his company.' It is an action picture, for that was what Rembrandt wanted - not a stiffly posed, artificial head count, as these pictures so often turned out to be.

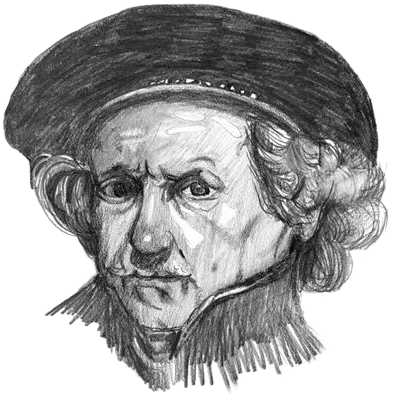

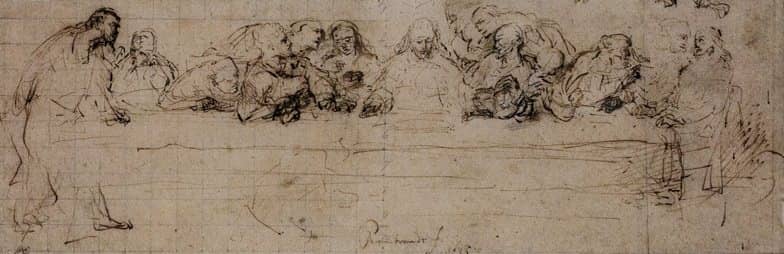

Many of Rembrandt's most prestigious commissions came from associations and groups with which he had professional contacts and led to the creation of some of his finest works. Group portraits of the governors and leaders of such groups were very popular commissions for artists. Rembrandt had studied in detail copies of The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci and this had been a crucial step in the development of his understanding and execution of the group portrait.

Rembrandt kept the painting dark, because where there is darkness, light can be provided: on the Lieutenant's yellow gold uniform, on the little girl in the second row. Exaggerated by a deteriorating varnish, this darkness caused the

picture to be called the Night Watch in the eighteenth century. Since the restoration of the painting, when all the old varnish was removed, it is quite plain that, for all the shadow, it is actually a 'day watch'.

Rembrandt subtly incorporated a number of facts about the militia company into his painting. The Arquebusiers from time immemorial had used firearms as their weapons, first arquebuses and later muskets. Accordingly Rembrandt worked into

the picture the various actions necessary for the use of a musket: the man in red in the left foreground is charging his musket with powder, just behind Van Ruytcnburgh's head a musket is being discharged, and a man on Van Ruytenburgh's

right is cleaning his musket by blowing the powder out of the pan. Because of the pun upon the sounds klover (arquebus) and klauw (talon), the Arquebusiers bore two bird's talons in their coat of arms: hence the chicken with its talons

hanging from the belt of the little girl, the company's mascot, who also carries the company's silver drinking horn, just visible beside her head.

On the shield above the gate are the names of the militiamen portrayed by Rembrandt, nineteen in all, since the drummer was allowed to be included without payment. Two of them are no longer present, since the left edge of the painting

was cut off in the early eighteenth century, when the Night Watch, together with the other militia paintings, was transferred to the Amsterdam Town Hall. The place that had been reserved for the Night Watch was a little too small,

and the picture was trimmed on three of its sides.